2025 Qualifying Quiz

-

A number is a palindrome if it reads the same backwards and forwards. For instance, 14541 is a palindrome, whereas 321 and 6560 are not. (Note that you can't write 6560 as 06560 to make it into a palindrome: zero is not a valid leading digit.)

Is it possible to write 2025 as a ratio of two palindromes? What about 2026?

-

Angela has just landed in the city of Metropolis. Her plan is to take the subway from the Airport station to the Museum station. Angela knows the following facts about the Metropolis subway system:

- It has 15 lines, all of which are straight.

- Every pair of subway lines intersects. Where they meet, there's an interchange station where you can switch from one line to the other.

- Each station is the interchange station between exactly two different lines. (No three lines meet at the same station.)

- A ride of n stops costs n subway tokens. (So if A and B are consecutive stations, riding between them costs one token.) Switching lines doesn't cost extra.

Unfortunately, Angela forgot to look up how far the Museum station is from the Airport station, and she has to buy tokens before she can consult a subway map.

- What is the smallest number of tokens Angela can buy to guarantee that she can get from the airport to the museum? (She'll have access to a map once she buys the tokens, so she'll be able to take the actual cheapest route.)

- Extra credit: What if Angela cannot assume that all the subway lines are straight? (We do not have a complete answer to this question, but we're curious what you can come up with.)

-

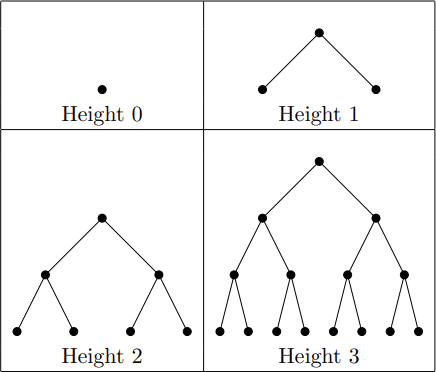

This problem is about perfect binary trees. The first few examples of perfect binary trees are shown below.

In general, a perfect binary tree of height n consists of n+1 rows of nodes (which are depicted as circles in the above figure). The top row has one node, called the root, and each subsequent row has twice as many nodes as the previous row. The 2n nodes in the bottom row are called the leaves. Each node except the root is connected by an edge to one node in the row above it, and each node that is not a leaf is connected by an edge to two nodes in the row below it.

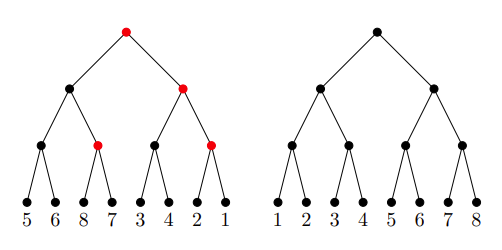

We can shuffle a perfect binary tree by deciding, for each non-leaf node, whether to switch the left and right branches coming out of that node. For example, in the diagram below, the tree on the right can be obtained from the tree on the left via a shuffle in which we switch the left and right branches from the nodes marked in red.

Suppose the leaves of our tree are labeled with some permutation of the numbers 1 to 2n, and we shuffle the tree to get as many leaf nodes as possible into the "correct" position (where the node's label corresponds to the node's number starting from the left). For example, our diagram shows that if n=3 and the starting permutation is 56873421, we can get all the leaf nodes into the correct position by shuffling. On the other hand, if the starting permutation is 18234567, we can't get all the leaf nodes into the correct position, since 1 and 8 would still be neighbors under any shuffle.

In the worst case scenario, for a perfect binary tree of height n, how many of the 2n leaf nodes can you get into the correct position by shuffling? (Note: If your answer is X, then you need to prove two things: (1) for any starting permutation, you can always get at least X nodes into the correct position by shuffling; (2) there are starting permutations for which you cannot get more than X nodes into the correct position by shuffling.)

-

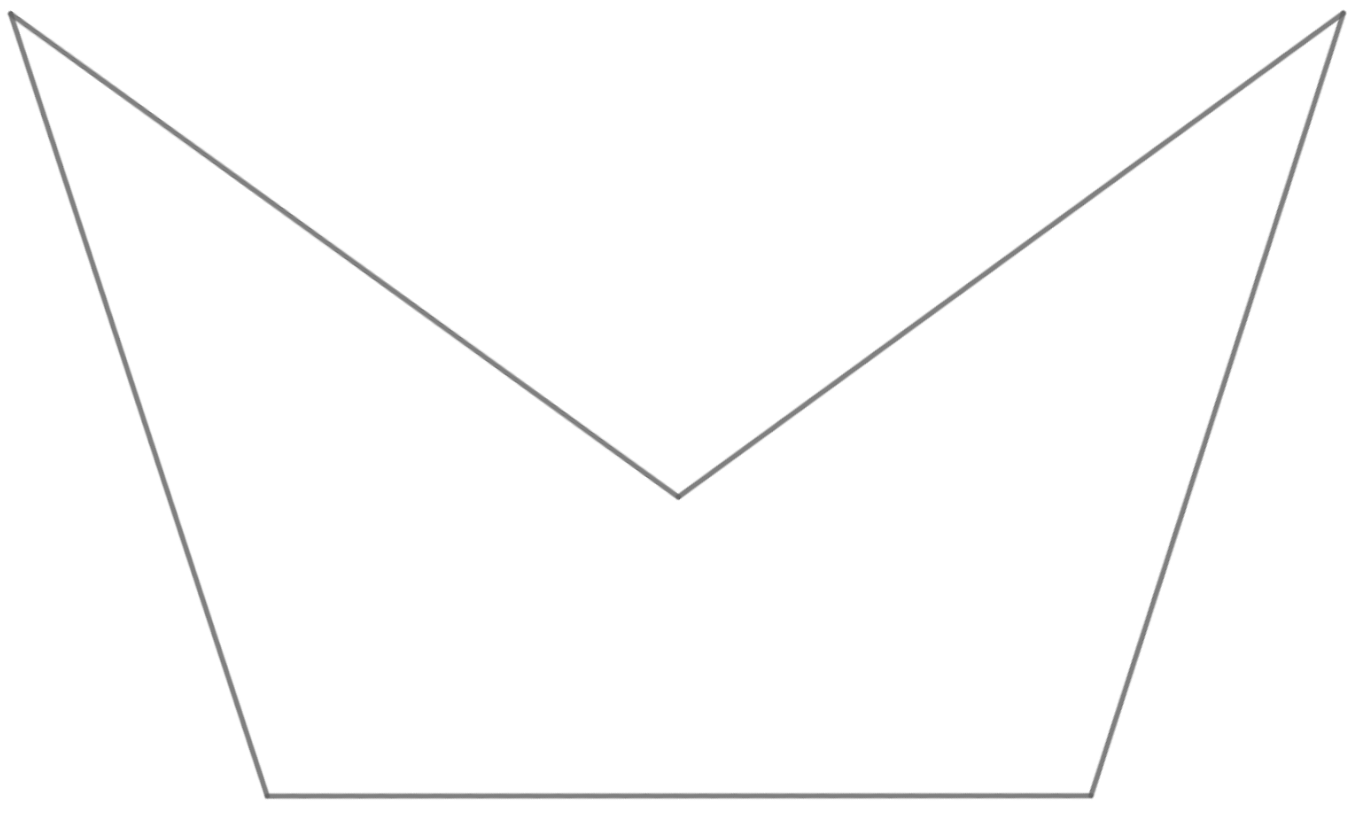

A crescent is a pentagon with five sides of equal length and internal angles 108°-36°-252°-36°-108°. This is just like a regular pentagon, but with one of the corners "caved in":

Show that it is possible to make a 12-sided polyhedron each of whose faces is a crescent.

(You might find it helpful and/or fun to make a paper model; if so, we'd love to see a photo! However, a model is not a proof: you still need to show that all the lengths and angles work out precisely. One way to do this is to specify the coordinates of the vertices, and then check everything that needs to be checked. We suggest centering your polyhedron at (0,0,0) to take advantage of symmetry.)

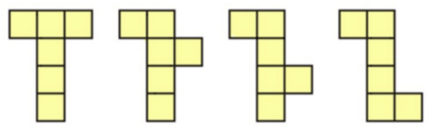

A net for a polyhedron is a connected arrangement of polygons in the plane that can be folded along a subset of the edges to create the polyhedron. For example, here are a few possible nets for a cube:

Is it possible to make a net for the polyhedron that you constructed in part (a)? Keep in mind that the twelve crescents forming the net are not allowed to overlap (except at the edges).

The state of Infiana is an infinite plane of farmland, subdivided into an infinite square grid of 1 km × 1 km plots of land. A finite number of farmers (at least two) each own infinite territory in Infiana, with each 1×1 plot belonging to exactly one farmer. The plots that each farmer owns are connected by orthogonal adjacency; in other words, any two points belonging to the same farmer can be connected by a road that lies within that farmer's territory and that does not pass through a vertex of a 1×1 plot along the way.

A farmer may split their territory into two fields by building a fence along the gridlines, all within their own territory. The laws of Infiana dictate that the fence must be of finite length, but the resulting fields must still have infinite area. Each field can then be further subdivided into more fields.

- For each positive integer n, give an example of a territory that can be split into n pieces but no more.

- Prove that no territory can be broken up into infinitely many pieces.

- Prove that there are always at least two farmers who cannot split their territory at all.

The Hilbert Curve is a famous example of a space-filling curve. (You can read all about it on Wikipedia, though you don't need any of that information to solve this problem.) Inspired by the Hilbert curve, Misha decides to build an infinite running track of the same shape. Instead of making the segments smaller and smaller so that the whole thing fits inside a 1×1 square, he makes all the segments 1 meter long and allows the track to extend over the entire first quadrant of the plane.

The track is constructed in stages, as follows:

-

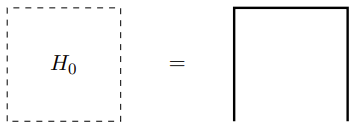

The initial stage H0 starts at (0,0) and covers the bottom left 1×1 square of the first quadrant. It consists of three segments in a U-shape:

-

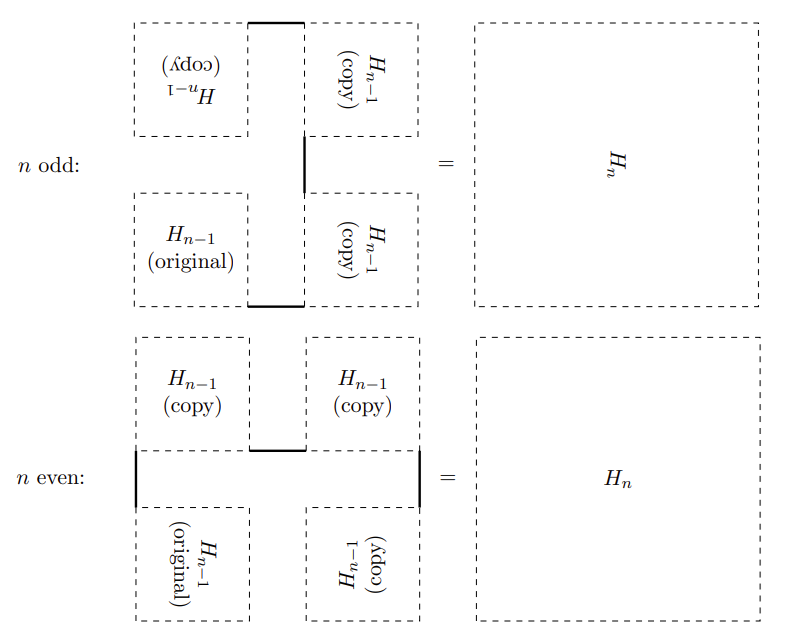

For each positive integer n, the stage Hn starts at (0,0) and covers the bottom left (2n+1-1)×(2n+1-1) square of the first quadrant. It begins with Hn-1, then continues with three rotated or reflected copies of Hn-1 joined together with line segments of length 1, as shown below:

Note that the procedures for constructing Hn for even and odd n are essentially the same. We display them separately to emphasize that when n is odd, the construction results in Hn appearing sideways (reflected about the line y = x).

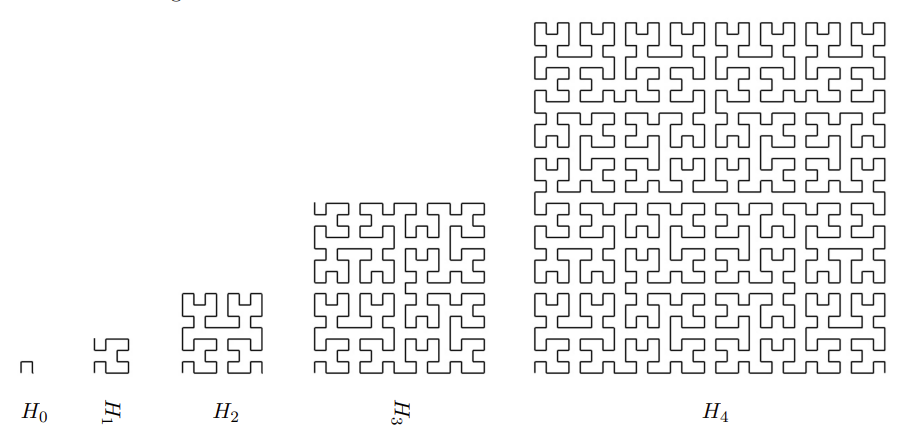

The first few stages of the construction are shown below:

(Image from https://www.designcoding.net/hilbert-curve/.)

General hint for this problem: it helps to write all distances along the running track in base 4.

- Warm-up: how long is Hn?

- How far along the track does a runner travel to get to the point (n,n)? (Hint: try it first for n = 2k.)

- One interesting feature of this running track is that you sometimes pass within a 1-meter distance of points that are very far ahead of you along the track — or very far behind! Suppose Anna, Benny, and Charlotte all start from (0,0) at the same time. Anna strolls at 1 m/s, Benny walks at 2 m/s, and Charlotte jogs at 3 m/s. Which pair(s) of them will pass within 1 meter of each other infinitely often? (Provide a proof both for the pairs that do and for the pairs that don't!)

- Della and Ellie each take a stroll along the running track at a speed of 1 m/s. Ellie starts k seconds after Della, where k is a positive odd integer. Show that there is some value of k such that Della and Ellie never pass within 1 meter of each other.

Problems 1, 2, and 5 are by Benny Wang (MC'24). Problem 3 is by Anna C. (MC'23). Problems 4 and 6 are by Misha Lavrov (Mathcamp staff).

FAQ Answers

Many applicants asked us questions to clarify the statements of Quiz problems via our QQ helpline. Here are some of the questions and our answers; you might find them helpful!

Problem 1

Can the numbers in question be decimals?

No, Problem 1 is just about integers.

Problem 2

What does "a ride of n stops" mean? Do the first and last stations count as stops?

The number of stops is the number of times the train stops after you get on it. In other words, the station where you get on doesn't count, but the station where you get off does. (This is standard terminology used by people who ride buses and trains.)

For example, suppose A, B, C, and D are consecutive stations on a line. Then a ride from A to B is 1 stop and would cost 1 token. A ride from A to C would cost 2 tokens (1 stop from A to B, one more stop from B to C), and a ride from A to D would cost 3 tokens.

If C, E, F are consecutive stations on a different line and you go from A to F by switching at C, then your ride would cost 4 tokens: 2 stops from A to C, 2 stops from C to F, and no cost for switching lines.

Can we assume that a pair of lines intersect each other no more than once in part b?

In 2b, a pair of subway lines can intersect any nonzero number of times, but exactly one of these intersections is a station.

Problem 4

In Problem 4a, to show that the required polyhedron exists, the problem says that we can "specify the coordinates of the vertices, and then check everything that needs to be checked". But what exactly needs to be checked here? If you look up the definition of "polyhedron" on Wikipedia, it states: "Many definitions of 'polyhedron' have been given within particular contexts ... and there is no universal agreement over which of these to choose." So what do we actually need to prove?

For the purposes of this problem, to show that a particular set of points form the vertices of the required polyhedron, you need to specify twelve 5-tuples of points that correspond to the faces of your polyhedron and then prove that each of these 5-tuples does indeed form a "crescent" as defined in the problem. (Technically, before you conclude that the resulting shape is a polyhedron, there is a lot more that would need to be verified -- e.g. each edge belongs to exactly two faces, each pair of intersecting faces meets only at a vertex or an edge, etc. But you don't need to prove any of those on the Quiz.)

We are more interested in how you structure your argument than in the details of your calculations. So if you have a lot of similar calculations, you can just give the details for one and say that the others are analogous. And definitely feel free to appeal to symmetry when appropriate.

In Problem 4a, can I use a calculator / Desmos / 3D modeling software in my proof that the required polyhedron exists?

If you're using any of these tools, then you've probably already figured out the coordinates of the vertices. So, as explained in the previous answer (see above), what remains is to specify which 5-tuples of vertices form faces and to prove that these faces are crescents. However, since the coordinates of the vertices involve irrational numbers, any computations on a calculator, Desmos, or most other software would be only approximate, hence insufficient for a proof. In this sense, a 3D model in Desmos is basically equivalent to a paper model: it's great for visualization and checking your intuition, and if you've made it, you should include it in your solution. But because it's only an approximation, it's not a proof.

In Problem 4b, can you cut some of the edges between adjacent faces in the net?

Yes, you can, as long as your net still remains a single connected piece. (I.e. you should be able to go from any face to any other face in the net via the uncut edges.)

Problem 5

Is every plot of land in Infiana owned by some farmer?

Yes.

Can you explain the condition "any two points belonging to the same farmer can be connected by a road that lies within that farmer's territory and that does not pass through a vertex of a 1×1 plot". Does the road have to be straight?

No, the road does not have to be straight. It just has to cross from one plot to another through edges, not vertices. This condition is meant to ensure that all the plots in a single territory are connected via edges ("orthogonal adjacency"). So you can't have a territory that consists of two pieces joined only by a single vertex: to get from one of those pieces to the other, the road would have to pass through the vertex, which is not allowed.

Do the laws of Infiana require that the total amount of fencing on a farmer's territory be finite, or does the law only apply to an individual fence?

The law only requires that each individual fence be finite; it does not say anything about the total length of all the fences.

I think I found a counterexample to 5b: an example of a territory that can be subdivided into an infinite number of pieces. (Several people have asked this question, all with essentially the same counterexample.)

The statement in 5b is true. If you think you have a counterexample, it must violate one of the problem conditions. Reread the problem carefully!

Problem 6

In 6c and 6d, should we consider the cases where the people are within 1 meter of each other during a non-integer time in seconds?

Yes, non-integer times do count.